The value of diary writing goes far beyond personal use

The value of diary writing goes far beyond personal use

by June Alexander

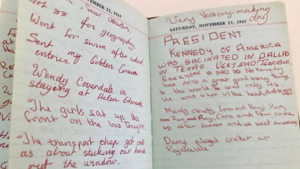

Little did I know at age 11 that a small Christmas gift of a diary would shape my life.

This diary immediately became a firm friend. A private relationship evolved between the pages and me. We bonded and faced life together. The process of letting thoughts and feelings tumble onto each new page, was like talking with myself. There was no guide book. The only other diarist I knew of was Samuel Pepys, who had lived centuries earlier, 1633-1703. In early grades at my one-room rural school, I was fascinated to read Pepys’ firsthand descriptions of the Great Fire of London.

Pepys’ diaries, to this day, provide a window into daily life at a certain place and time. Not until I was much older would I look beyond the diary entry I wrote each day, and start to appreciate that the daily writing habit I had developed in childhood was part of a long tradition.

The diary works as a thought-sifter

French professor and essayist, Philippe Lejeune connects the growth of the diary form starting in the late Middle Ages with two major time-keeping developments – the mechanical clock and the annual calendar. Between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, these inventions enabled diarists, like Pepys, to record life in a series of daily reflections. Of course, as Lejeune explains, a diarist does not write every second of the day – the daily entry for a 24-hour period might be written in 10 minutes. In this way, the diary works like a sieve with the writer choosing what to include, and in what way.

The diary’s worth lies in what the diarist records, and what is left out. Lejeune likens the diarist to an artisan, like a sculptor or an artist, who decides what material to include and in so doing, shapes their work. This process of sifting, reflection and contemplation, deciding what to keep and to discard, day after day, creates a valuable means for the diarist preserving moments of their life in their diary.

A series of dated references

Lejeune defines the diary as ‘a series of dated traces’ (2009, p 179). The ‘trace’ is usually writing, but may also be an object, drawing or picture, which, when part of a series, embraces the movement of time. Rather than describing a one-off event, the diary’s strength lies in being ‘methodical, repetitive and obsessive’ (p 179) allowing threads to emerge and form patterns over time. Although uninhibited in choosing what to write, the diarist’s accumulation of daily fragments, through repetition and regularity, create their own emphasis, patterns and rhythm.

Through my PhD research, I planned to study diary excerpts, to identify and reveal patterns and rhythms that occur when an eating disorder develops. I wanted to explore the disconnection that occurs between body and self and healing and how the reconnection with self might start to take place. Analysis of such excerpts would involve appraising the texts themselves, and placing them in context over a period of time.

As noted by Lejeune, (2009, p 178) the diary represents freedom in the recording of thoughts, yet is regimented, defined by the clock and calendar. As such, it also represents a genre of exploration, providing a method for internal reflection and observation, and external analysis.

Feminism’s role in raising the diary’s profile

Lejeune’s enthusiasm for the diary as a literary genre was not universal, however. For centuries, diary writing had received little systematic attention as an activity or commitment, or on what it meant to be a diarist. The American writer Susan Sontag (1933–2004), whose diaries comprised almost 100 notebooks (Maunsell, 2011), was among several writers (e.g. Vera Brittain, Anäis Nin, Virginia Woolf) leading up to and during the rise of feminism in the 1960s, who raised the profile of the diary (which had been seen as a subsidiary to other literary works) as a document worthy of respect in its own right, as a genre.

The work of Sontag on the illness experience has also been influential, for she continually strove to both gain deeper insight and care of herself through her diary writing, as well as hone her literary skills (Maunsell). I related strongly to Sontag’s experience, because while my diary helped me to survive my eating disorder, until I accessed professional help, it also helped to prolong it. My diary then proceeded to become a valuable ongoing self-recovery tool, which continues to this day. (For more discussion on interest in women’s diaries by feminist and women’s studies scholars, and on women’s history, see Alexander, Brien et al.)

Diaries are much more than mere records

While Lejeune put forward a succinct definition for the process of creating a diary, for a long time scholars did not know what to do with them. Their potential largely went unnoticed. Private diaries, Paperno (2004) posits, with their blend of personal observations, reflections and facts, elude defined structure both as a genre and cultural phenomenon. Alaszewski (2006) contends diaries are much more than mere records of events, feelings and a witness to suffering; they also are imaginative, creative works, and a foundation for new works. Indeed.

Whether or not you choose to share your diary writings with others, either in their original form or as a basis for other literary work, your diary remains a valuable record and keepsake of your life, your experiences, your thoughts and feelings, at particular moments in time.

Not so private on the Internet

More recently, the diary, due to developments on the Internet since the 1990s, has entered an ambiguous area between public and private life. The diary’s functions in this context have been explored, interpreted and applied in numerous ways. Today the diary genre continues to reflect its pre-modern understanding, where diary writing was considered a deeply private and personal activity, shared with close others if at all, but also embraces the online forms of diary writing, where entries may be shared publicly, and readers may be unknown.

Whether the diary comprises a traditional private pen and paper volume, or online format, it can be considered as a means for thinking ‘through the seam between the private and the public self’, allowing the self to emerge through the writing process rather than necessarily as a reflection of the diarist’s real experience (Serfaty, 2004, p. 462).

My main interest in this history of the diary was to explore the diary’s evolution as a recording tool of daily activities and events, and as a repository and an outlet for mental and emotional stresses, as this was the focus of my creative work, Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders, The Diary Healer.

References

- Alaszewski, A. (2006). Diaries as a source of suffering narratives: A critical commentary. Health, Risk & Society, 8(1), 43-58.

- Alexander, J. (2011). A Girl Called Tim _ Escape from an Eating Disorder Hell. Sydney: New Holland Publishers.

- Alexander, J. (2016) Using Writing as a Therapy for Eating Disorders _ The Diary Healer. London: Routledge Mental Health.

- Alexander, J., Brien, D. L., & McAllister, M. (2015). Diaries are ‘better than novels, more accurate than histories, and even at times more dramatic than plays’.

- Lejeune, P. (2009). On diary (J. D. Popkin & J. Rak Eds.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Maunsell, J. B. (2011). The writer’s diary as device: The making of Susan Sontag in “Reborn: Early diaries 1947-1963”. Journal of Modern Literature, 35, 1-20. doi:10.2979/jmodelite.35.1.1

- Paperno, I. (2004). What can be done with diaries?, 561.

- Sontag, S. (2008). Reborn: Journals and notebooks, 1947-1963: Macmillan.

- Serfaty, V. (2004). Online diaries: Towards a structural approach. Journal of American Studies, 38(3), 457-471. doi:10.1017/S0021875804008746